Background

The first Europeans to make paper of their own were from the Kingdoms of Northern Spain early in the 12th century though the process was possibly still Oriental or Arabic in character. By the 13th century paper makers in Italy already practised a distinctively European process making use of rags, a rigid mould with a wire cover and gelatine sizing. It was nearly 500 years later that the main features of this process were to alter and papermaking technology underwent a radical change in direction. The main element in this was a new method, developed in Holland in the mid-17th century, for converting rags into pulp.

Papermaking, and White paper at that, was introduced into England ca. 1490, but had a spasmodic early history because resources were limited and manufacturing conditions uneconomic compared with those on the continent.

England in the 17th Century was a small kingdom with a population only a quarter of the size of its powerful neighbour, France, a country which had abundant resources and well-regulated industries. It was thus disadvantaged from the outset when attempting to set up an economically competitive White paper industry, faced as it was by a shortage of raw materials, skilled craftsmen, and, more important in the context of these books, severe restrictions on printing. Despite the lifting of these controls in 1695 the market place in the early decades of the 18th Century was still dominated by imports of paper from the continent, but this time they came from a vigorous and technologically superior industry in the Netherlands.

As the 18th Century progressed two features were to reverse this situation: first, the introduction of increasingly punitive rates of Duty reduced the level of imports and thus protected the struggling White paper manufacture from extinction; and, second, greatly improved productivity and quality, resulting from advances in papermaking technology, enabled the domestic products to compete with and, ultimately, gain ascendancy over their foreign equivalents.

The Elder James Whatman, by John Balston

In 1992 John Balston published a major study of these advances in papermaking technology and the key role that the elder James Whatman played in their application.

Earlier work by the author had shown that Whatman's invention and development of Wove paper near the end of his life was a more considerable technological achievement than had been recognized formerly.

This book posed the questions, who was this man, nominally a tanner until 1740, and whence had he acquired expertise of this order in another trade?

No previous accounts had ever placed Whatman in a contemporary papermaking setting. To give him a three-dimensional background it was essential

- to summarise the evolution of the domestic industry from its inception to the early 18th century (a complex transition from an entrepreneurial basis to one controlled by paper makers); and

- to examine the origins of the industry in his locality at Maidstone, Kent (never attempted previously), an industry that emerged from virtual non-existence to become one of the principal centres in the country over a period of some 40 years, partly during Whatman's childhood and formative years. Solutions were suggested for both his seemingly miraculous overnight transformation from tanner to paper maker in 1740, occupying a position of pre-eminence from the very beginning of his papermaking career, as well as for his gaining an unassailable reputation for the quality of his paper in the British market, a place habitually denied to the domestic producer.

The isolated position of Kent is well suited to a study of this kind. By following the regional growth of the industry from a very scattered and meagre platform, particularly the dramatic expansion at Maidstone, together with the succession of occupants in the mills, it soon becomes apparent that one is dealing with a papermaking community and an industrial entity that became a nursery for papermaking in the 19th Century.

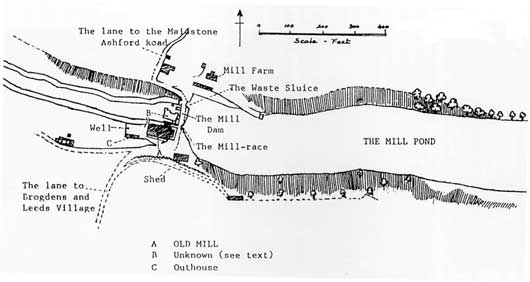

The Old Mill at Hollingbourne - part of a sketchmap showing the plan about 1880

The vatman about to dip a paper mould into the vat. From the Encyclopédie of Diderot, 1751-1777.

The same action photographed in the

20th century